First Oxygen Ion collisions at LHC

From July 2nd to 5th, I made a short but memorable trip to CERN, where—for the first time in its history—the LHC collided oxygen ions. For several years, I have been a strong advocate for the unique physics opportunities presented by light-ion collisions at the LHC. Witnessing these collisions take place was a deeply rewarding moment.

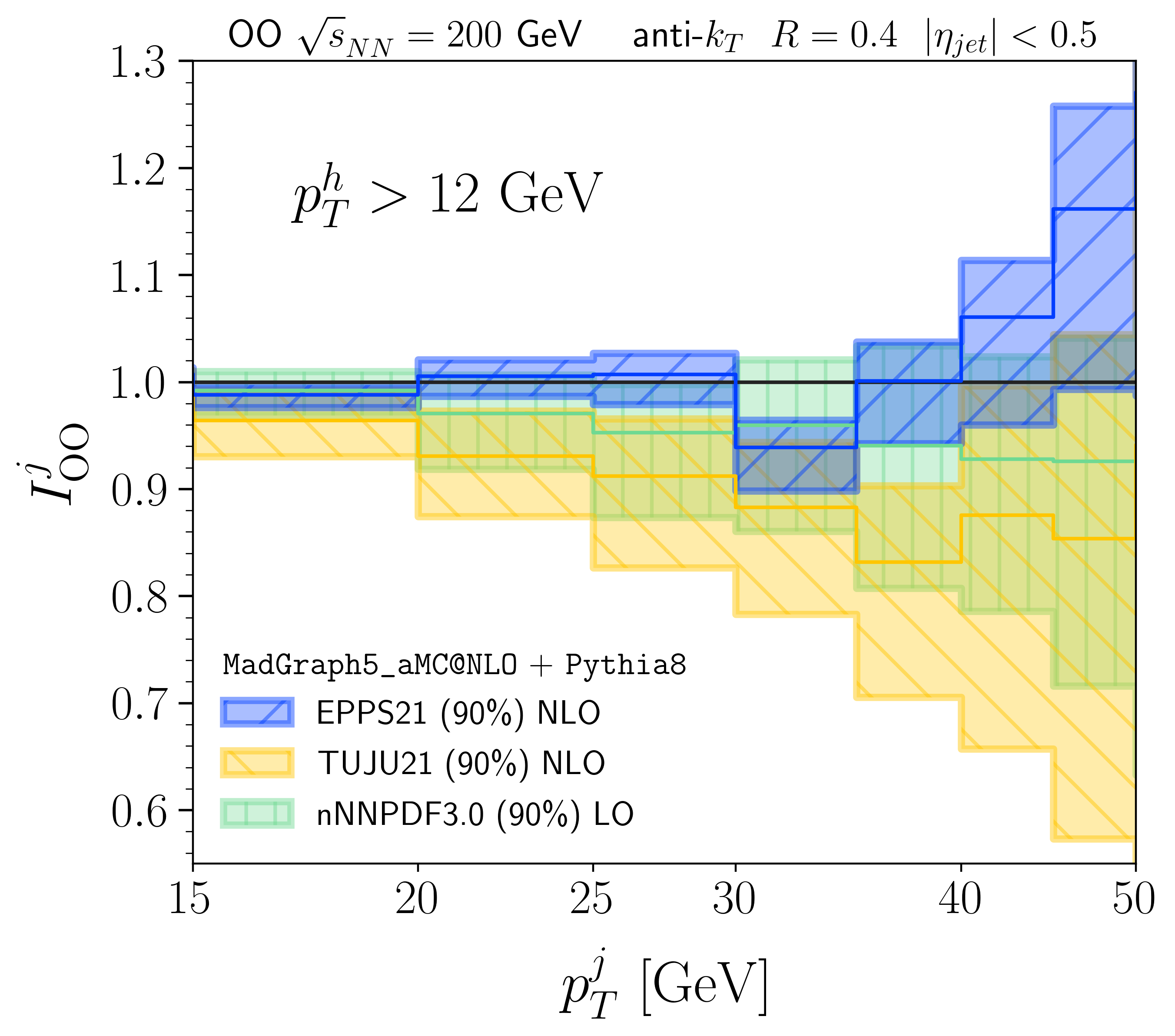

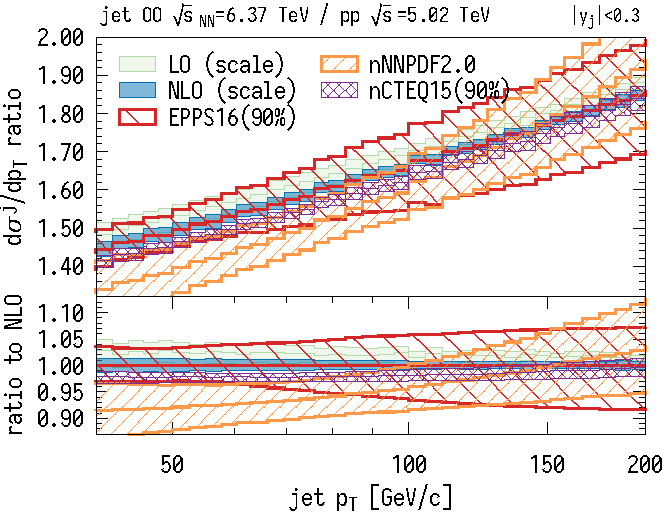

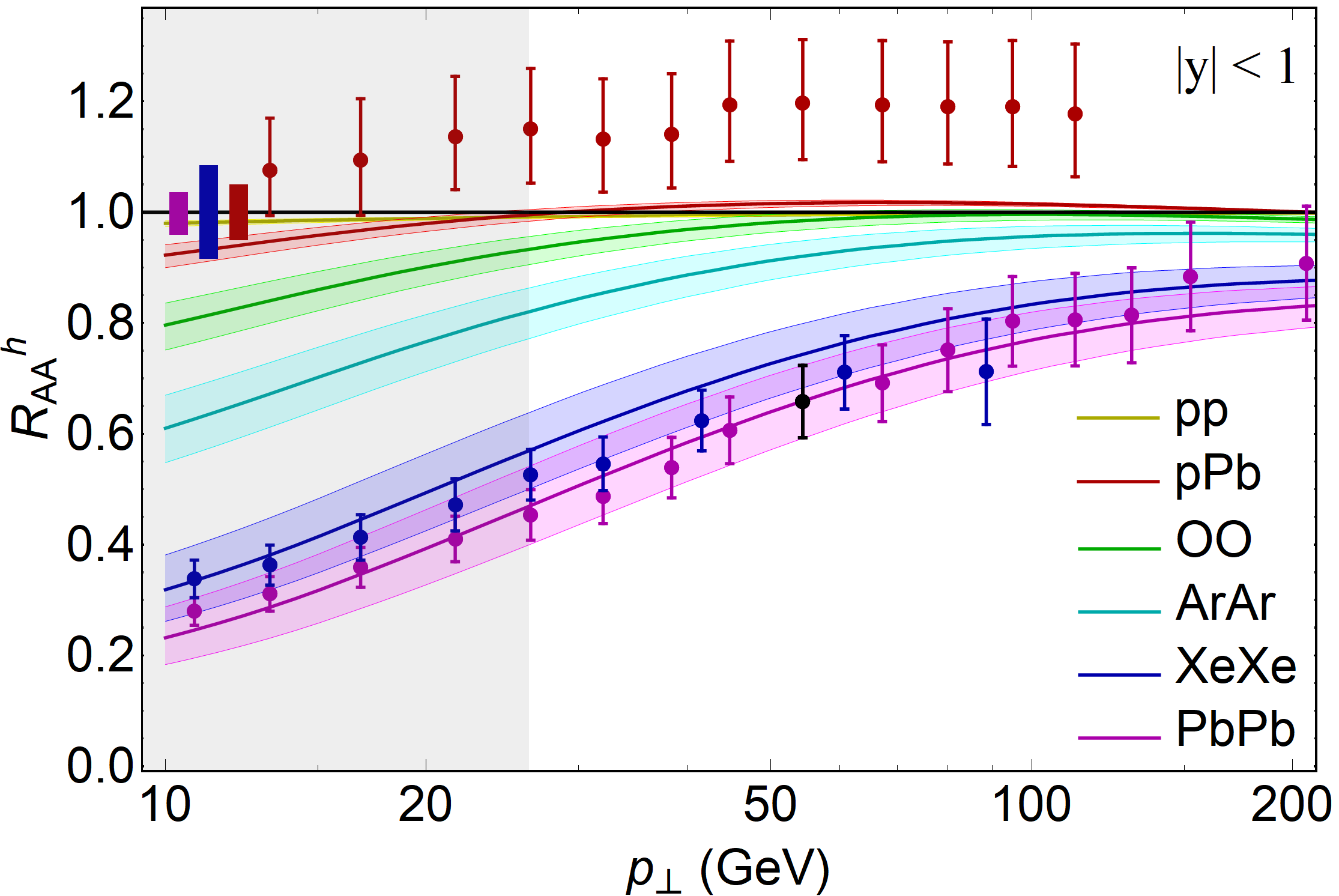

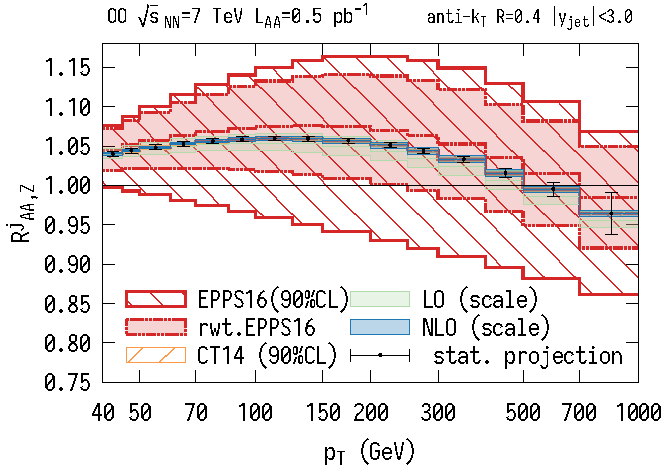

More than five years ago, during my time as a CERN Fellow, we identified that the planned oxygen-oxygen (OO) collisions could provide an ideal testing ground for observing high-momentum energy loss signals in small systems—still an outstanding problem in the field. Following our publications (Huss et al., 2021; Huss et al., 2021), I co-organized a workshop on the physics opportunities of proton-oxygen and oxygen-oxygen collisions and presented the physics case to the LHC Committee. I went on to publish two more papers on observables in these systems (Brewer et al., 2022; Gebhard et al., 2024). Over time, community support for a dedicated light-ion run solidified, and the collisions finally took place during the first week of July.

Remarkably, the run also included a one-fill session of neon-neon collisions, enabling comparative studies of nuclear shape effects between oxygen and neon. This opportunistic addition became possible thanks to colleagues who made a strong physics case and to accelerator physicists who demonstrated that a rapid switch to neon was feasible.

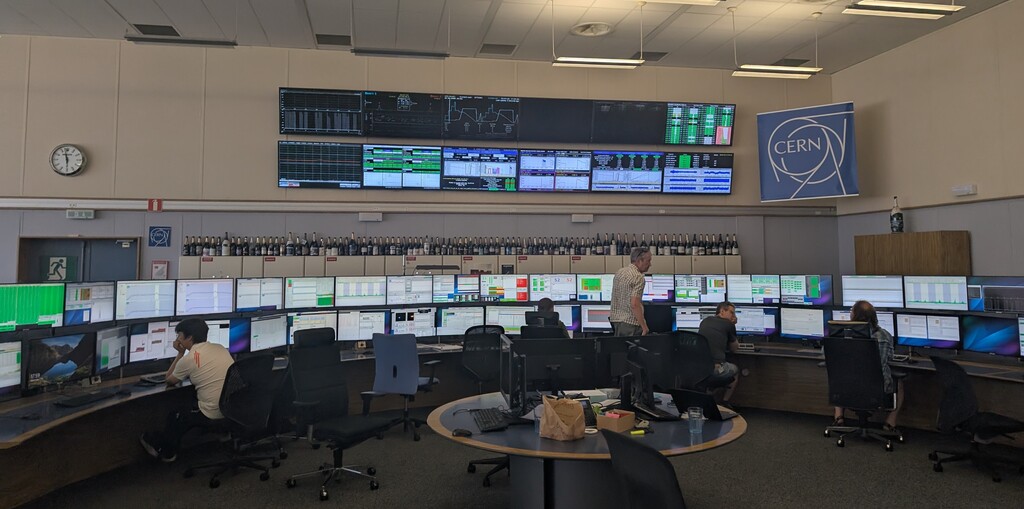

During the oxygen run, I was fortunate to receive private tours of both the CERN Control Centre (CCC) and the ALICE Control Room. It was my first time visiting the CCC in Prévessin, which oversees the entire CERN accelerator complex. The room is enormous—lined with hundreds of monitors controlling everything from injections to cryogenics. I was particularly impressed by the fast turnaround of particle beams in the PS and SPS accelerators, which supply proton and ion beams to a wide array of CERN experiments. Once the LHC is filled, it may take 8–12 hours before the next injection, during which time experiments across the complex—including in the North Area—are conducted.

Though the LHC is CERN’s flagship machine, it’s important to remember that the infrastructure supports a broad range of scientific studies, from medical isotopes and cosmic ray physics to cloud formation and neutrino research.

At the CCC, I learned more about how beams are accelerated and monitored. Lighter ions like oxygen bring unique challenges. If my theory-trained brain understood correctly, their lower mass makes it harder to keep the ions bunched due to stronger electric repulsion. Partially stripped oxygen ions are also more prone to colliding with residual gas in the beam pipe. These are non-trivial challenges that accelerator physicists must overcome to achieve high-luminosity beams.

While I was at the CCC, the accelerator was running proton-oxygen (pO) collisions—important for cosmic-ray studies, with dedicated measurements taken by the LHCf detector near ATLAS. A large dataset was collected, which will also help calibrate the subsequent OO collisions.

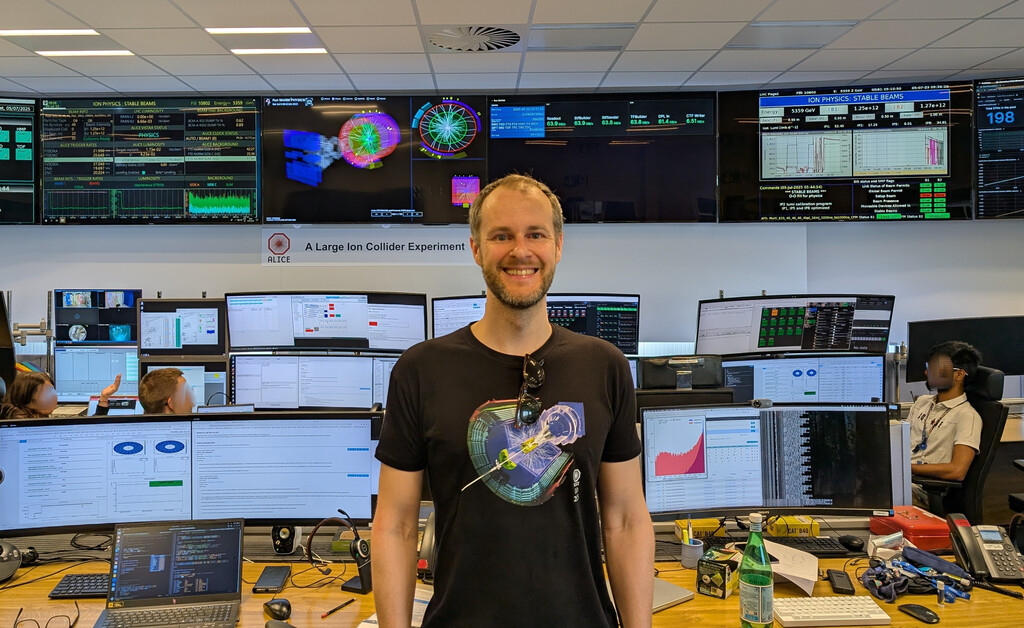

A Night at ALICE

On the evening of July 4th, I headed to the ALICE Control Room, anticipating the very first oxygen-oxygen collisions at the LHC. I got a firsthand glimpse of the patience and vigilance required from experimental physicists. A small in-person crew monitors detector performance, data quality, and safety protocols, backed by a larger group of on-call experts available around the clock. Crews rotate in 8-hour shifts to ensure non-stop data collection.

The LHC, being the most complex machine in the world, requires strict safety protocols. Even small deviations trigger automatic beam dumps to protect both the machine and the experiments. I arrived around 8 p.m., but the first declaration of stable beams was delayed—first to 11 p.m., then to midnight.

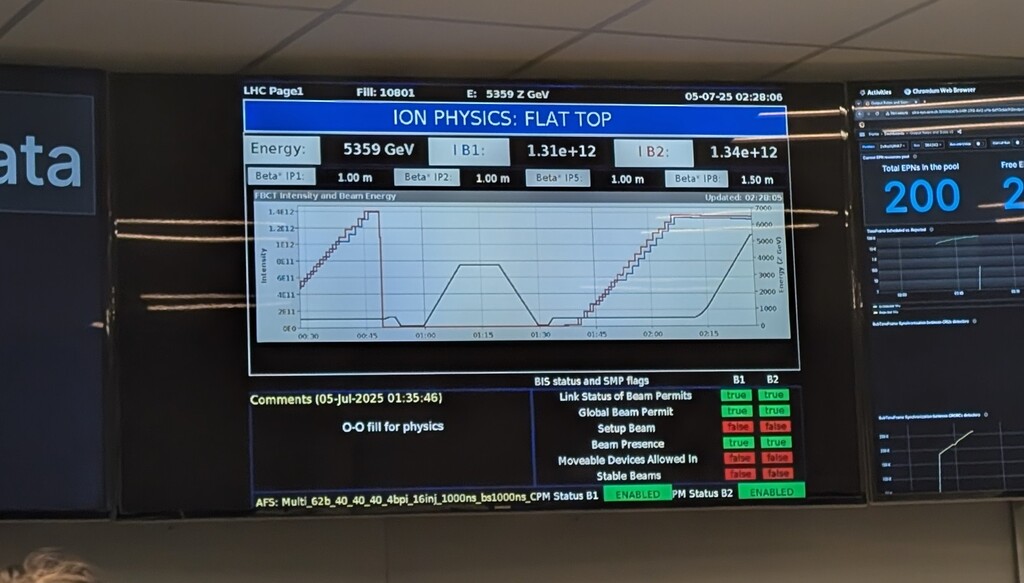

Finally, around 12:15 a.m., the first OO physics fill began. The beams are injected in stages, in bunches, over about 30 minutes. Then they must be accelerated from the injection energy (450 GeV) to the collision energy (5360 GeV), matching that of previous Pb-Pb collisions and, more importantly, the pp reference energy.

Because the LHC’s physical ring is fixed, its magnetic field must increase with beam energy to maintain the particles’ circular path. However, just as the ramp-up phase began, the beam was lost. Something I hadn’t known: once ramping starts, the magnets must complete the entire cycle—even without the beam—ramping all the way up and back down. This ensures the magnets reach their full field strength safely.

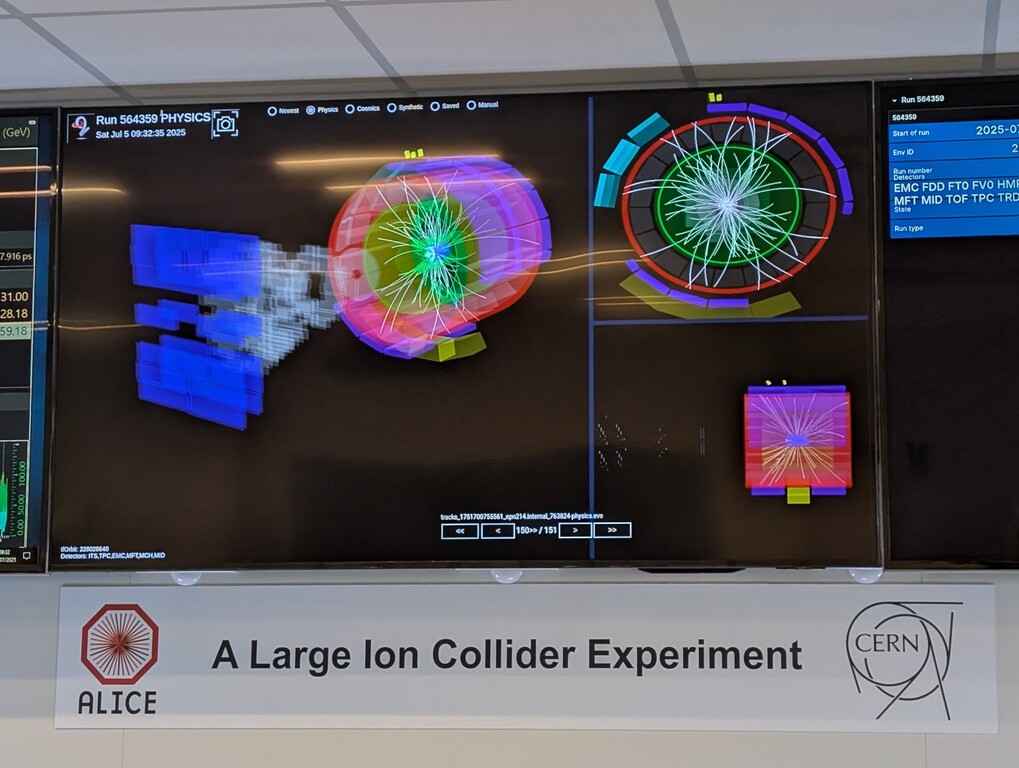

This procedure meant we had to wait another hour before a second beam fill. Fortunately, this time the ramp-up was successful, and at 2:30 a.m. on Saturday, the oxygen beams reached their target collision energy. We all waited for the official declaration of stable beams—the signal for detectors to switch from standby to active data collection mode.

Unfortunately, another issue triggered a beam dump just before data taking could begin, restarting the cycle. At that point, I decided to get some rest, leaving the ALICE crew to handle the overnight shift. By 5 a.m., stable beams were finally achieved. I returned later in the morning, just to take a selfie with live OO collision events! I even received a special OO run t-shirt—a gesture I really appreciated. In the end, the OO run was a resounding success. All experiments collected far more data than the minimum requirement.

What’s Next: Neon and Beyond

I returned to Heidelberg that Saturday, but just a few days later, the LHC was filled with neon. Despite some technical hiccups, a long fill of neon-neon collisions was successfully carried out. The next phase is the data analysis frenzy: internal calibration, unfolding, estimating statistical and systematic uncertainties—all before any results are made public. This process can take anywhere from a few months to years, depending on the observable.

However, we can expect the first preliminary results to be shared at the upcoming Initial Stages conference in Taipei, which I’m particularly excited about for two reasons. First, I’ve been invited to give a plenary talk on predictions and interpretations for OO and pO collisions—an incredible honor. Second, I’ve developed a baseline prediction for the nuclear modification factor of charged hadrons, under the null hypothesis that no QGP is formed in OO collisions. If experimentalists observe a statistically significant deviation from this baseline, we could claim the discovery of energy loss in systems with just ~10 participating nucleons on average—a potential breakthrough.

Final Thoughts

In summary, it has been an incredibly rewarding experience to be part of the collective effort that contributed to running the world’s most advanced scientific experiment. It’s deeply inspiring to be surrounded by curious minds, all motivated to push the frontiers of knowledge and overcome technical challenges. This spirit, as CERN proudly puts it, is accelerating science.

References

2024

2022

2021

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: